Cassette tape types

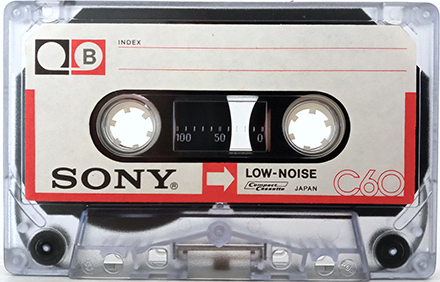

Type I

Normal

Type I, or IEC I, ferric or 'normal' cassettes were historically the first, the most common and the least expensive; they dominated the prerecorded cassette market. Can be used by any tape recorder or player. Pre-recorded cassettes tend to use ferric tape and all Walkmans can play it correctly. Recording on ferric tape requires only a moderate amount of energy and this is the type of tape that should be used in recording Walkmans. Magnetic layer of a ferric tape consists of around 30% synthetic binder and 70% magnetic powder - acicular (oblong, needle-like) particles of gamma ferric oxide (γ-Fe2O3), with a length of 0.2 μm to 0.75 μm. Each particle of such size contains a single magnetic domain. The powder was and still is manufactured in bulk by chemical companies specializing in mineral pigments for the paint industry. Ferric magnetic layers have brown colour, its shade and intensity depending mostly on the size of particles. Type I tapes must be recorded with 'normal' (low) bias flux and replayed with 120 μs time constant. Over time, ferric oxide technology developed continuously, with new, superior generations emerging around every five years. Cassettes of various periods and price points can be sorted into three distinct groups: basic coarse-grained tapes; advanced fine-grained, or microferric, tapes; and highest-grade ferricobalt tapes, having ferric oxide particles encapsulated in a thin layer of cobalt-iron compound. Remanence and squareness of the three groups substantially differ, while coercivity remains almost unchanged at around 380 Oe (360 Oe for the IEC reference tape approved in 1979). Quality Type I cassettes have higher midrange MOL than most Type II tapes, slow and gentle MOL roll-off at low frequencies, but less treble headroom than Type II. In practice that means that ferric tapes have lower fidelity compared to chromes and metals at high frequencies, but are often better at reproducing the low frequencies found in bass-heavy music.

Type II

CrO₂

IEC Type II tapes are intended for recording with high (150% of normal) bias and replay with 70 μs time constant. All generations of Type II reference tapes, including the 1971 DIN reference that pre-dated the IEC standard, were manufactured by BASF. Type II has been historically known as 'chromium dioxide tape' or simply 'chrome tape', but in reality most of Type II cassettes do not contain chromium. The "pseudochromes" (including almost all Type II's made by the Big Three Japanese makers - Maxell, Sony and TDK) are actually ferricobalt formulations optimized for Type II recording and playback settings. A true chrome tape must have a distinctive hot wax smell, which is missing in "pseudochromes". Both kinds of Type II have, on average, lower treble MOL and SOL, and higher signal-to-noise ratio than quality Type I tapes. This is caused by midrange and treble pre-emphasis applied during recording to match 70μs equalization at playback. Chrome and Metal tapes are played in the same way so some Walkmans have the switch labelled with just one of them, normally Metal. Chrome tape requires more energy to record on, so simple recorders, such as the WM-BF67, cannot use it for recording. Chrome cassettes have extra slots in the back which some players can recognise and adjust themselves automatically, for example the WM-F75.

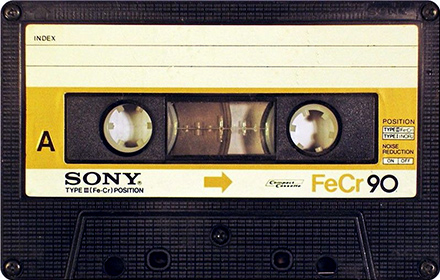

Type III

FeCr

In 1973 Sony introduced double-layer ferrichrome tapes, having a five-micron ferric base coated with one micron of CrO₂ pigment. The new cassettes were advertized as 'the best of both worlds' - combining good low-frequency MOL of microferric tapes with good treble performance of chrome tapes. The novelty became part of the IEC standard, codenamed Type III; the Sony CS301 formulation became the IEC reference. However, the idea failed to attract followers. Apart from Sony, only BASF and Agfa introduced their own ferrichrome cassettes. These expensive tapes never gained substantial market share, and after the release of metal tapes they lost their perceived exclusivity. Their place in the market was taken over by superior and less expensive ferricobalt formulations. By 1983, tape deck manufacturers stopped providing Type III recording option. Ferrichrome tape remained in BASF and Sony lineups until 1984 and 1988 respectively. The use of ferrichrome tapes was complicated by conflicting rationale of the playback of these tapes. Officially: they were intended to be played back using 70 μs equalisation. The information leaflet that Sony included in each box of the ferrichrome cassette recommended that, "If the selector has two positions, NORMAL and CrO₂, set it to the NORMAL postion." (which applies 120 μs equalisation). The leaflet notes that the high frequency range will be enhanced and that the tone control should be adjusted to compensate. The same leaflet recommends that if the playback machine offers a 'Fe-Cr' selection, that this should be selected. On Sony's machines, this automatically selects 70 μs equalisation. Neither Sony nor BASF cassettes feature the notches on the back surface that automatically selects 70 μs equalisation on those machines that featured an automatic detection system.

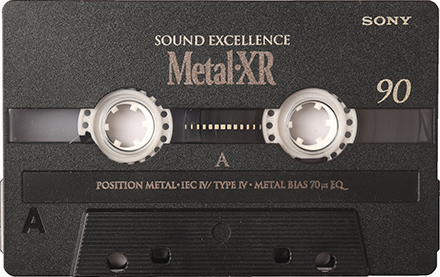

Type IV

Metal

Pure metal particles have an inherent advantage over oxide particles due to 3–4 times higher remanence, very high coercivity and far smaller particle size resulting in both higher MOL and SOL values. First attempts to make metal particle (MP), rather than metal oxide particle, tape date back to 1946; viable iron-cobalt-nickel formulations appeared in 1962. In early 1970s Philips began development of MP formulations for Compact Cassette. Contemporary powder metallurgy could not yet produce fine, submicron size particles, and properly passivate these highly pyrophoric powders. Although the latter problem were soon solved, the chemists did not convince the market in long-term stability of MP tapes; suspicions of inevitable early degradation persisted until the end of cassette era. However, most metal tapes survived decades of storage just as well as Type 1 tapes; however, signals recorded on metal tapes do degrade at about the same rate as in chromium tapes, around 2 dB over the estimated lifetime of the cassette. Metal particle Compact Cassettes, or simply 'metals', were introduced in 1979 and were soon standardized by the IEC as Type IV. They share the 70 μs replay time constant with Type II, and can be correctly reproduced by any deck equipped with Type II equalization. Recording onto a metal tape requires special high-flux magnetic heads and high-current amplifiers to drive them. Traditional glass ferrite heads would saturate their magnetic cores before reaching these levels. "Metal capable" decks had to be equipped with new heads built around sendust or permalloy cores, or the new generation of glass ferrite heads with specially treated gap materials. Metal tape is difficult to record on and the only Walkmans capable are the WM-D6 and the WM-D6C. Metal tape has the same identification slots as Chrome, so those Walkmans with automatic tape selectors can detect and adapt settings.